The Story So Far…

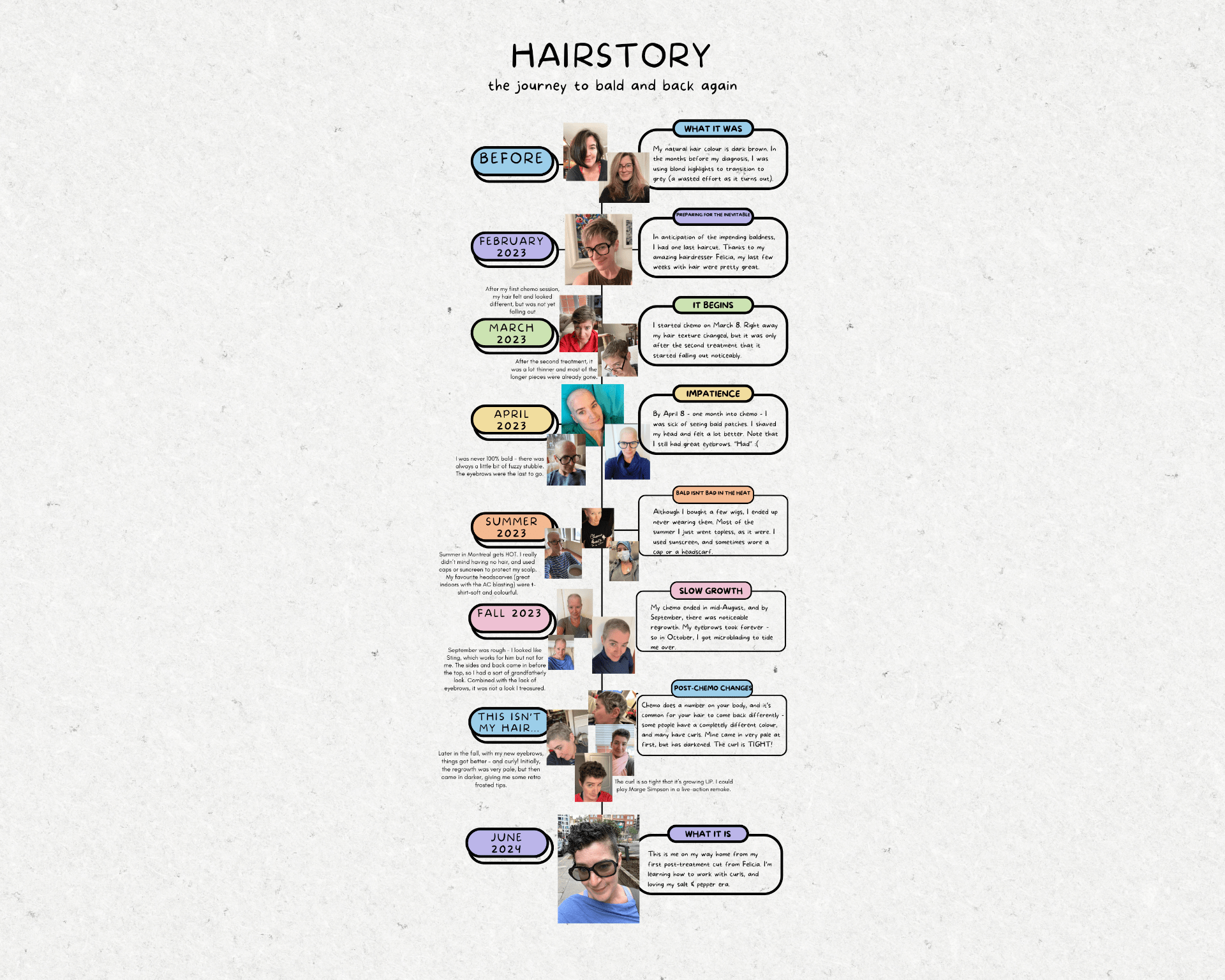

In February 2023, I was diagnosed with breast cancer. I began six months of chemotherapy in March 2023, and a year of Herceptin in June 2023. I had a mastectomy, in which my right breast was removed, in October 2023.

At that point, my options were to have a breast reconstructed using my own tissue (known as a flap procedure), have a breast implant, or have a very lopsided bosom. The waitlist for the flap procedure was at least a year, so I opted for the implant, and had that surgery in February 2024.

That should have been it – the Herceptin treatment ended in June 2024, and I returned to work, happy to have it all behind me.

The problem, as I have explained here before, was that my body essentially rejected the implant. Once again, my options were as above – a flap, a new implant, or no implant at all. This time, I elected to wait for the flap. The wait was indeed over a year; I was put on the list in March 2024, and finally got the call for my surgery date in June 2025.

On June 25, 2025, I had what I very much hope was my last cancer-related surgery.

The Gory Details

A flap procedure is so called because the surgeon takes a flap of tissue from one part of your body and uses is to reconstruct another area. The two most common breast reconstruction flap procedures – the DIEP and the TRAM – both use tissue taken from the abdomen.

This is not a matter of sucking fat from your belly and injecting it into your breast – some cosmetic surgeries do use that kind of technique, taking fat from one area to plump up another, like the breasts or buttocks. Instead, a flap procedure involves skin, fatty tissue, blood vessels, and sometimes muscle; the key to a successful flap is continued blood flow through the tissue after it has been transplanted. In the photo, the section of skin inside the suture line was originally abdominal tissue. The major advantage of this procedure, as opposed to the silicone implant, is that the risk of infection and other complications is greatly reduced, since your body is dealing with its own tissue, rather than a foreign object.

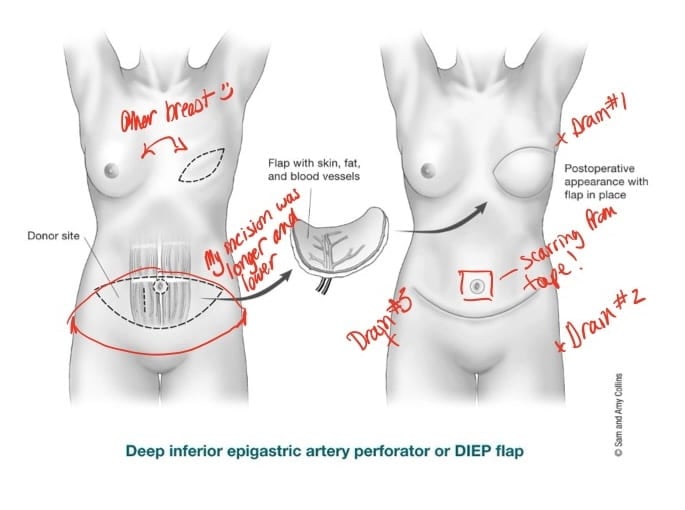

Taking tissue from the abdomen is a big job – in my case, the surgeon cut out an elliptical section of tissue with a symmetrical incision from hip-to-hip. The bottom part of the ellipse lands just above my pubic bone, and the top would have been part way between my bellybutton and my sternum. Once that section was removed, the surgeon pulled down the remaining skin from the top of my abdomen and stitched it to the skin at the pubic bone line (see image below, with my notes), and made me a new bellybutton in the appropriate location.

Post-op

I spent four days and nights in the hospital. The first night, following the 8-hour procedure, was essentially just sleeping off the anaesthetic. The nursing team was a little concerned because my blood pressure was consistently very low, but we discovered in the morning that there was a slow leak in the cuff, and I was not, in fact, crashing.

The morning after the surgery, I was moved from the recovery room to my own private room (a fantastic feature of the new MUHC is the default private room, which I imagine makes hospital-borne infections much less prevalent). For the first 24 hours, they used a small Doppler ultrasound device to check for blood flow through the transplanted tissue; they continued checking this, at less frequent intervals, throughout my stay.

When I came out of surgery, I had three drains attached: one on my back just under my arm to drain fluid from the breast surgical site, and one on each upper thigh, close to either end of the abdominal incision. I also had a gauze and tape dressing over the new bellybutton, more dressing under my breast, and dressings across my abdomen over the incision and around the drain insertion sites. I also had an abdominal binder.

On the second or third day after the surgery, I mentioned to my nurse that I had a bad itch under the dressing around the drain close to my breast; she checked and discovered a blister was forming under the dressing. And that’s how we found out I am allergic to surgical tape! I love that at 56 I’m still learning new things about myself.

The nurse and one of the surgical team removed all my dressings – which meant I also got to see the extent of the incision for the first time, which was… interesting – and replaced everything with new gauze and a different kind of hypoallergenic tape. This allergic reaction might not sound like a big deal, but to illustrate, when they removed the dressing from around my bellybutton, there was a red welt under each piece of tape, so I had a pretty gruesome outline. That was six weeks ago, and there’s still a distinct red line around my bellybutton.

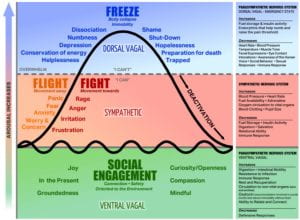

I was encouraged to walk around the ward, which I did, very slowly. The first few outings I had to use a walker, because I had a colostomy bag, and because I literally could not stand up – the skin on my abdomen was so tight that I couldn’t straighten my torso at all. I slept sitting up; even after I was home, I slept sitting up for at least a week. In fact, last night – again, six weeks post-op – was the first night that I slept in my usual flat-on-my-stomach position. Once the colostomy bag was removed, I walked around the ward using my IV pole to support my upper body. Walking was relatively easy but my back was in agony, because I was so hunched over that the weight of my head was too much for my lower back. Once I was home, I used two canes to support me for another week or so. The abdominal tightness and the restrictions it imposed were the most unexpected aspect of my recovery. Six weeks later I can walk unassisted (in fact, for the last week or so I have made a point of taking a long walk every day, and I am happy to say that my strides are getting more and more comfortable) but my belly is still very tight, and movements like back or side bends are very limited.

The Home Stretch, As It Were

I was cleared to go home four days after the surgery, and they removed the drain from the breast site before I left the hospital. I was sent home with prescriptions for opioid pain killers, Tylenol, multivitamins, and a month-long course of daily injections of a blood thinner called Fragmin, to avoid clotting in the new boob. I was also given a couple of the abdominal binders, with instructions to wear one ALL THE TIME, for WEEKS. I have not followed this instruction, because the binders are uncomfortable, and not because they bind your abdomen, but because they are too wide, so they irritate the incision under my breast, and they roll up from the bottom so they’re never actually correctly placed over my abdomen. Instead, I have been wearing high compression leggings or shapewear, and everything seems to be in place – no hernias, no weird bulges, no sagging.

I had a follow up with the surgical nurse five days after I left the hospital, during which the nurse change my dressing and checked the drains, and another follow up the next Wednesday. At this second follow up, the nurse removed the drain from my left hip, but the drain on the right was still collecting a lot of fluid so it stayed in. The nurse was very pleased with my recovery, and she said everything seemed to be progressing very well.

Naturally, this was my body’s cue to enter disruptor mode.

That Thursday evening, I felt terrible. I developed a fever, and had chills and aches and nausea to the point of vomiting. Friday morning, I called the post-op patient support line, and described the symptoms – including a fever that spiked at 39.8° C (103.6° F). The nurse I spoke to advised me to take my pain killers and prescription Tylenol and monitor my symptoms (I had a follow up with the surgeon coming up on Monday), and to go to the emergency room only if the fever went back up to the 40° C range. The nurses from the patient support line called me back on Saturday, twice, to let me know that they had spoken to my surgeon and to check on me; again, the advice was to wait for my Monday appointment unless things took a bad turn.

At the Monday appointment, the surgeon confirmed that there was an infection (duh), and I was given a prescription for antibiotics. Everything else looked good though, and the antibiotics did their job and I was back on track in a day or two. He did not remove the final drain, which was still collecting a lot of fluid (blood, clots, and thanks to the infection, pus. Bodies are gross). I had yet another follow up with the surgical nurse later the same week; at this appointment, we realised that my body was reacting to the suture that was keeping the drain in place (!) because the skin around the suture was red and sore and oozy. So she removed the suture (not the drain) and Macgyvered a way to keep the drain in place with tape (hypoallergenic, of course), and sent me home with instructions to email her if anything changed.

I emailed her the following Monday, and posited that the drain itself was potentially a problem. After all, if my body was reacting to silk sutures and other medical-grade materials (including, historically, temporary tissue expanders and silicone breast implants), why wouldn’t it be reacting to the plastic tubing of the drain? There was still pus coming through the drain, even though I was almost done with the antibiotics, so, I said, either we should remove the drain, or extend the prescription. She wrote back, after consulting with the surgeon, and the following afternoon she removed the drain and I was free!!

That was July 22, almost exactly a month after the actual surgery.

Now that there are no more foreign objects in or on my body, I am healing well and getting stronger every day.

I have yet another follow up in two weeks, but I am optimistic – finally – that this is indeed my last surgery, and I can finally put this ridiculous chapter behind me. I will continue to have mammograms for my left breast, and likely ultrasound scans for the right breast, but I am fortunate to not have any long-term prescriptions, so essentially, I am back to “normal,” whatever that means.

And oh, the plans I have for scar-camouflaging tattoos…